Safe School Checklist

PHOTO COURTESY OF MOBIKEFED

I've turned out more than a few checklists over the years, some voluminous, (for the encyclopedic version, visit ncef.org) and others mercifully brief. If you like them short and sweet, try this one:

- Nobody can step onto school property, or enter a school building, without being seen and immediately assessed as to whether they pose a threat.

- Nobody can physically get into any of the buildings, through any doors or windows, without consent.

- All classrooms can be immediately secured during lockdowns, without requiring teachers to step into the hallways and manipulate keys.

- All classrooms have secondary escape options, either through emergency doors or windows, if egress is needed.

- Communication devices make it easy to reach staff, students and visitors in a timely manner.

Not a bad list, truly. If you’ve got all those points covered at 100 percent, you’re well ahead of the game. Congratulations! You deserve a raise.

But wait! We’re just getting started. Now follow up with a slightly different, more refined approach:

- Pose very specific, basic scenarios, then

- Craft very specific solutions.

In many schools, safety planning starts with generalities, like: “prevent school shootings, trespassers, bullying and vandalism.” With such broad goals, solutions are likely to be equally generic — better locks, more cameras and perhaps a few campus monitors, for example. But that leaves plenty of room for fine-tuning. For example, identify your top three real life concerns. Try to be as specific as possible. These can range from highly unlikely but catastrophic events, (i.e. “no more Columbines,”) to highly likely, but less newsworthy challenges (i.e. “Keep kids from knocking over the candy machine.”)

Here are some more examples of specific problems to solve:

Keep threatening individuals from:

- entering school grounds from behind the bus barn;

- entering via the patio at lunchtime;

- proceeding past the entry foyer between 7:30 A.M. and 8:00 A.M.

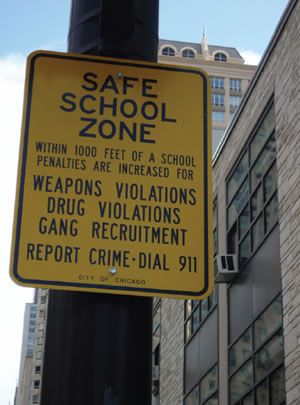

This list can be further refined to address particular troublemakers, such as non-custodial parents, specific students recently expelled for bringing guns to school or local gang recruiters.

Stopping bullying:

- on the playground during recess;

- in the back hall between classes;

- in the outdoor bathroom next to the gym.

Again, this can be more focused on particular offenders with predictable schedules and distinct motivations.

Stopping vandalism:

- between midnight and 6 a.m.;

- on the gym wall most weekends;

- of the seventh-grade, west-wing windows.

PHOTO COURTESY OF AMBERNECTAR 13

Lower Your Risks. Creating a safe school checklist is an important first step in improving the safety of your school. To get even greater results, create a checklist that includes detailed, specific components. Once you have a list, start working with in-depth scenarios. These two last steps will help you cover areas that the original list may have missed.

You guessed it — getting specific can help you fine tune solutions. Graffiti might help identify specific culprits. Perhaps someone has claimed the area adjacent to the gym as turf. Or maybe one student really hated seventh grade.

Addressing specific problems yields insights that checklists might miss.

Now let’s dig a little deeper, using in-depth scenarios. Here’s one example.

Last Tuesday, Charlie Epsom burst into Mrs. Newsom’s physics classroom, intent on harming Sam Tork, who was falsely rumored to be dating Charlie’s ex-girlfriend, Zoe Brains. Other kids had given Sam a heads-up about Charlie’s intentions, so Sam had stayed home. Now, Charlie was convinced everyone was conspiring to protect Sam. He pulled out a gun and started waving it around while cursing loudly. At that point, Mrs. Newsom collapsed with an asthma attack. This distracted Charlie long enough for star athlete Susan Quigley to clobber Charlie with a well-aimed hockey puck. Charlie at that point dropped the gun, grabbed his forehead, and staggered into the hallway, bleeding profusely. Susan called 911 on her cell phone. The principal then received a call from the police, and subsequently used the intercom to order a lockdown. Police arrived five minutes later, followed the blood trail out the back door. With the help of a police tracking dog, Charlie was caught 20 minutes later, hiding in a playhouse behind Barnes Elementary school.

Now that we’ve painted a highly detailed picture of a specific scenario, we can conduct a much more useful assessment. Here are specific problems and their solutions:

Students heard about a threat, but nobody told parents or school staff.

- How can we make reporting easier?

- Can we add a physical or electronic drop box or tip line?

- Can we reinforce importance of reporting?

- Can we do a better job building rapport with students?

Charlie was able to bring a gun into school undetected.

- Do we know where he got the gun?

- Did his parents know he had a gun? Did they approve?

- Once he had the gun in a pocket or backpack, how could we have discovered it?

- Do we want to add the use of metal detector wands or portals?

- Can we determine how/when he got the gun to school?

- Could it have been passed through a window, or stashed in an outside hiding place for later retrieval?

- If he hid something on the grounds, or passed it through a window, or received it through a window, could a camera have picked it up?

- Is anyone watching the cameras?

Mrs. Newsom’s medical condition interfered with her ability to either intervene or call for help.

- Was Mrs. Newsom well enough to be at work?

- Should we have noticed earlier, and sent her home?

- Did she prefer to keep her medical condition private?

- Were staff aware of her medical condition?

- Were students aware of her medical condition?

- Did either group know what to do if she was incapacitated?

- What communication devices were available to her to call for help? Clearly they weren’t effective.

- What alternatives should be considered?

- Can she wear an emergency pendant?

Susan Quigley brought a weapon (puck).

- Is a puck a weapon under the policy or not?

- Are we obliged to treat it as such after the fact?

- What flexibility do we have?

- Is consistency here important?

Susan didn’t report to the nearest available staff member, or call the office by phone or intercom.

- Does the rule make sense under the circumstances?

- Is it realistic to think that students would read the handbook and remember the rules?

- Can we teach the rules, crisis responses and use of the intercom more effectively?

- Is the technology too confusing?

- Do we need to put instructions next to the phone?

- Can we add an emergency button that works like a speed-dial?

Charlie fled while dripping blood, a potential health risk and alarming to students.

- First aid supplies should be readily available in each classroom.

The office didn’t know what was going on until it was too late to do much about it.

- Can we provide an emergency pendant for Mrs. Newsom? Or for all teachers?

- Microphones and cameras that turn on in the classroom when a panic button is pushed, so the office can hear what’s going on?

Nobody thought to alert the nearby elementary school, or others at risk.

- We need to clarify with 911 that they should make that happen.

In assessing your school, by all means use broad-brush checklists to get things rolling. But for more refined results, follow up with in-depth scenarios. You’re likely to uncover problems and solutions initially missed.

Creating Safer Schools

The national crime prevention council (NCPC) has published a brochure entitled, National Crime Prevention Council Tips for Working Together to Create Safer Schools. It includes suggestions about what parents, school staff , students and the community can do to make schools safer places for everyone.

The section related specifically to school staff suggests the following.

“The school staff including the administration must be behind any effort to create a safer school. Here are a few ideas of how the school can be involved in this effort. School staff and administrators can evaluate a school’s safety objectively. Set targets for improvement. Be honest about crime problems and work toward bettering the situation. Develop consistent disciplinary policies, good security procedures and response plans for emergencies. Addressing the violence issue is difficult and complex; however, there are ways to create a safer environment in which to learn.

“Teens can’t do it alone because there needs to be a community-wide effort addressing the issue. They need help from others. But teens can take the lead. Creating a safe place where you can learn and grow depends on a partnership among students, parents, teachers and other community institutions to prevent school violence. Think about the issues that affect your school, and see how you or a team of people can make a difference in addressing the problem.”

The community also must be a part of any planning. The NCPC suggests that community partners, “Look to community partners to enrich and make your school safer. Law enforcement can report on the type of crimes in the surrounding community and suggest ways to make schools safer.

“Police or organized groups of adults can patrol routes students take to and from school. Community-based groups, church organizations and other service groups can provide counseling, extended learning programs, before- and afterschool activities and other community crime prevention programs. State and local governments can develop model school safety plans and provide funding for schools to implement the programs.

“Local businesses can provide apprenticeship programs, participate in adopt-a-school programs or serve as mentors to area students. Colleges and universities can offer conflict management courses to teachers or assist school officials in implementing violence prevention curricula.”

The NCPC suggests that action be taken by recruiting teens, parents, school staff and police to develop safe school task force, start a conflict resolution program in the school, and set up a group to allow teens to share problems and solutions.

For more information, visit ncpc.org. To see the brochure on working together, go to ncpc.org.

This article originally appeared in the School Planning & Management December 2013 issue of Spaces4Learning.